06 Dec The Feeling Value of Lines

This post is a blast from the past at my former blog, You Are Here. The content is still very much at the top of my mind, though, as I’m more interested than ever in the manner in which simple lines and contours might influence how we feel.

Sometime back in the 1990s when instamatic cameras were using new film formats and special features to try to get a little market cachet, I remember buying a not-very-expensive model on the way to visit a friend of mine for a weekend at the beach. I’ll always remember what he said when he saw the camera: “Colin, that looks like a Miata.” And it’s true — the camera had a very curvy and pleasing shape that just made you feel good when you looked at it. I just thought of this again as I poured myself a glass of pomegranate juice from that very distinctive double-globed bottle. I’ve never quite known what to make of the bottle. It does look somewhat pleasing to me, but it also looks somewhat disturbingly organic — let’s face it — it looks like organs. And it makes me feel slightly sad to look at the thing. I have no idea what the intent of the designers of the bottle might have been, but I would guess that it is meant to suggest that pomegranate juice is good for your body. But the sadness is interesting.

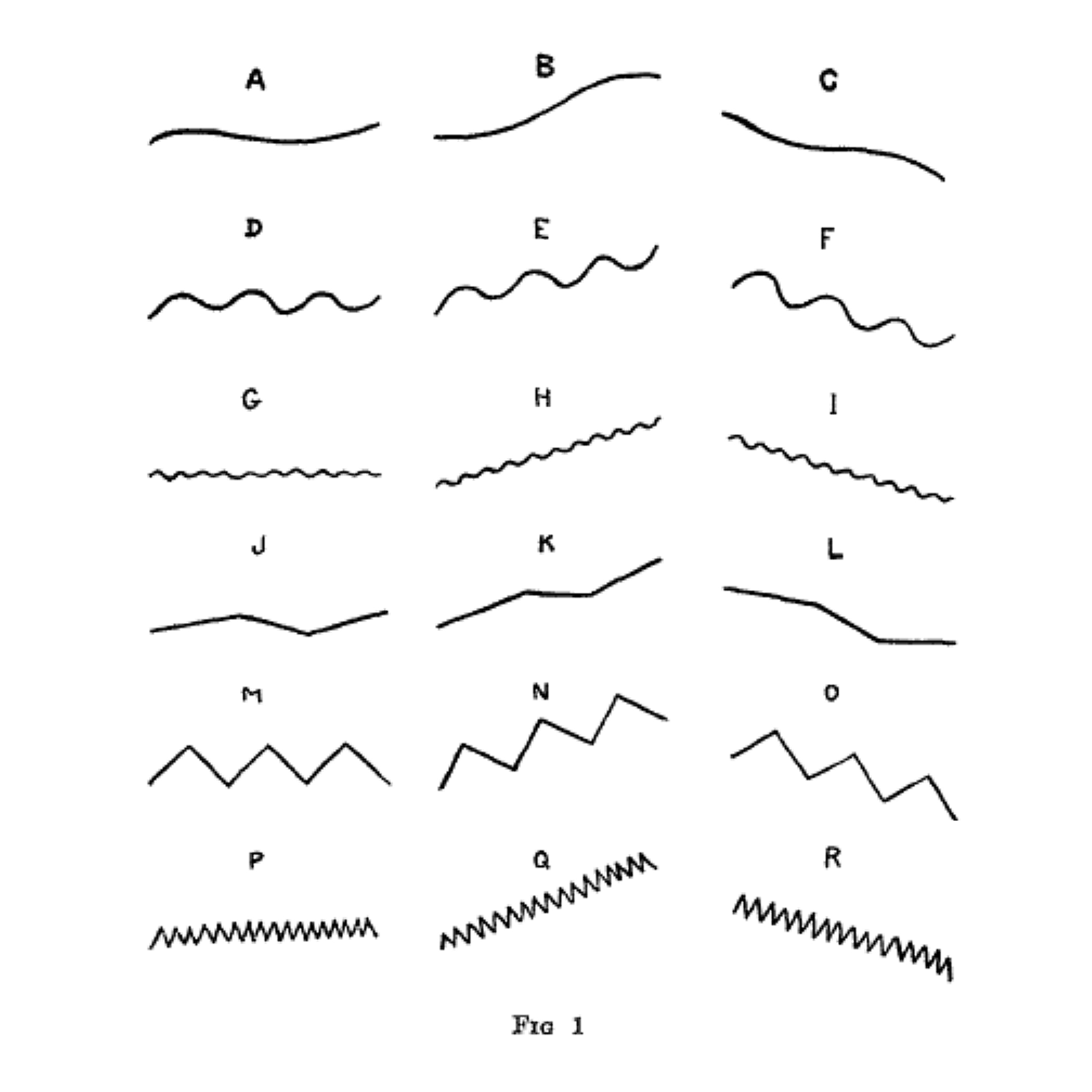

All of this reminded me of an old line of research that I first heard about last fall at the Design and Emotion conference in Chicago. The work wasn’t presented there but it was discussed in the broader context of how shapes and appearances make us feel. Poffenberger and Barrows of Columbia University published a paper in 1924 entitled “The feeling value of lines” in which they presented 500 observers with two things: a set of emotional adjectives (sad, quiet, lazy, playful, agitating, serious, merry, for example) and a set of very simple lines ranging from graceful curves to sharp-edged saw blades (the picture above shows examples of the contours used in the study). They asked the observers to simply indicate which of the emotions they associated with each of the lines. There was surprising universality in the results. Observers almost invariably saw downward graceful curves as being sad, and angles as being more powerful and agitating. And it’s interesting that I don’t even need to show you examples of these figures for you to shrug your shoulders and say ‘of course’.

So where does that ‘of course’ response come from and what does it mean?

Some theories of aesthetics suggest that some of our responses to patterns are deeply inbuilt biological responses that come from ancient circuits designed to respond to important events like the presence of predators or bounty, and I think it quite likely that some of our universality in responses to designs do come from such connections. But there’s another interesting possibility in the case of these lines, which was actually mentioned in the 1924 paper. Based on a theory of aesthetics described by Ethel Puffer, the authors suggested that when we observe a line, or really any other pattern, we make a series of movements to carry out the observation. Most obvious in the case of the lines is that our eyes follow them. The movements of our eyes as we follow the line produce feelings which, according to Puffer, we attribute to the lines themselves. So the feelings come from inside us and they are generated by the movements that we, ourselves, make as we observe the lines.

So why should a downward curving line produce eye movements that make us sad? Why should sharp angles make us anxious? Perhaps there’s a connection with emotional expression. When we feel sad, we cast our eyes downward, perhaps to reduce input from the external world. When we’re agitated, we move our eyes to and fro, surveying the world anxiously. In a strange way, it’s almost as if the lines are talking to us, encouraging us to express our own emotions in particular ways.

I’m going to look through my fridge and cupboards now to see what other feelings might be hiding in there.

Hugo Moreschi López

Posted at 17:46h, 17 JanuaryHi..! I´m an Industrial designer , I am reading one of your books, is very interesting because now I will write my master teases about design, bicycles and cities.

Best regards from Mexico.

DI Hugo Moreschi