22 Apr Taking a breath

A couple of years ago, I was recruited by a local church that was struggling with the same issues as most other Christian churches in the Western world – a decrease in attendance and membership, which in turn was leading to financial woes and a great deal of navel-gazing about the future. I don’t mean so much the church in its earliest sense as a gathering of believers and a religious community, because it was clear that there was still a strong commitment to that kind of community. The issues had to do with the maintenance of a beautiful but increasingly fragile and expensive-to-maintain piece of architecture. The news is filled with stories of such buildings being converted to more utilitarian purposes or even, in some cases, being torn down to build offices or condos. As an expert in the psychological experience of architecture, I was asked to help this group envision a new and financially viable future for their stunning sanctuary.

A couple of years ago, I was recruited by a local church that was struggling with the same issues as most other Christian churches in the Western world – a decrease in attendance and membership, which in turn was leading to financial woes and a great deal of navel-gazing about the future. I don’t mean so much the church in its earliest sense as a gathering of believers and a religious community, because it was clear that there was still a strong commitment to that kind of community. The issues had to do with the maintenance of a beautiful but increasingly fragile and expensive-to-maintain piece of architecture. The news is filled with stories of such buildings being converted to more utilitarian purposes or even, in some cases, being torn down to build offices or condos. As an expert in the psychological experience of architecture, I was asked to help this group envision a new and financially viable future for their stunning sanctuary.

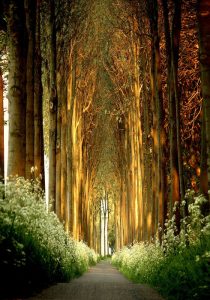

As I thought about what to recommend, my premise was that though there may be waning interest in attendance at regular Sunday services or participation in some of the traditional rituals of the church, I didn’t believe that this change was accompanied by a waning of spirituality. Even before the pandemic, there has been a rising hunger for spirituality. If anything, I believe that this hunger is now stronger than it has been at any point in my lifetime. But that word…. spirit…is so laden. Like so much of Western thought, the lineage of the word is wrapped up in theology. Though the idea of spirituality is probably as old as humanity, its use in the Old Testament, captured in the old Hebrew word ruach, meant breath or wind. Words like this make me prick up my scientific ears as they resonate with one of the central pillars of my scientific work –the idea that we are attracted to—even hard-wired to respond to—vitality. Spirit as the breath of life is the wellspring of our vital force which, as a crass empiricist I begin to break down into the science of neurons and synapses. But sometimes, like right now, I’d rather not.

Turning back to my architectural problem, the question was whether it might be possible to re-imagine this beautiful soaring sanctuary, a great vault filled with light and sound, as a space that might be open to anyone with an appetite to honour, sustain, or grow their own vital spirit regardless of their denomination. Could design measures open up that wonderful space to unimagined new uses? Could it house or even give birth to new kinds of spiritual communities? As a salient landmark in a downtown streetscape, could it be a central pillar in a new way of thinking about urban spaces dedicated to material or spiritual wellness? A beacon of empathy and compassion? In the end, I put together a set of ideas, made a presentation to the congregation, and I’d like to think that I made a small contribution to helping them find the courage to reimagine themselves and their built designs. I’m not really sure if I did. I don’t think the story has reached a conclusion yet, though I have seen some promising early steps.

As we launch ourselves into a new kind of future, leaning more than ever on digital life, pushing past the edges of a fleshless post-human existence and perhaps encouraged by our ability to keep some things (sort of) intact during a year-long lockdown, we may re-discover a deep craving for bodily engagement with one another, with an opportunity for the shared awareness of ruach, and an architecture that can contain it. Now that I’m a little wiser and perhaps a little bruised from my experiences with trying to advocate for a re-design of a traditional Christian space, I wonder whether the visual and spatial imagery of such a building is too strongly resonant of a culture and history that some of us may struggle to find comfort with. Perhaps it’s just too much to imagine such a space converting to a universally accessible non-denominational home for the human spirit. But that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a place in our cities for physical beacons of empathy and compassion. My work, along with much of the work done by others, has shown that buildings and their occupants, together, produce what we are calling architectural atmosphere (and there’s that air, wind or ruach showing up again….). But you don’t need me to tell you this, of course. I think everyone understands the idea that when you walk into a space, it can prime you to feel some particular way. That’s the kind of atmosphere I mean. But what’s remarkable about this kind of atmosphere is that it can change behaviour. Feelings of awe, for example, can make us kinder to one another. It’s hard to imagine a setting where that’s not a desirable end.

At a time when we are feeling more separated from one another than ever, when many are predicting that one aspect of post-pandemic existence could be a stimulus to think of new ways to be together and new ways to share, is it time to imagine new ways to build architectural houses for spirit and vitality

No Comments